Curtain-calls function as a natural transition between the production’s constructed reality, and our IRL reality that’s waiting for us as soon as the lights come up.

Curtain calls are the final note that a production ends on, the note that sends the audience back into our “real” world. Obviously we know what we’ve just seen is a performance, but the curtain call visually breaks the preceding artifice’s maintained illusion of truth. Even if the story concludes in the most depressing manner, watching the cast be lavished with praise as themselves at the very least interacts with that depression.

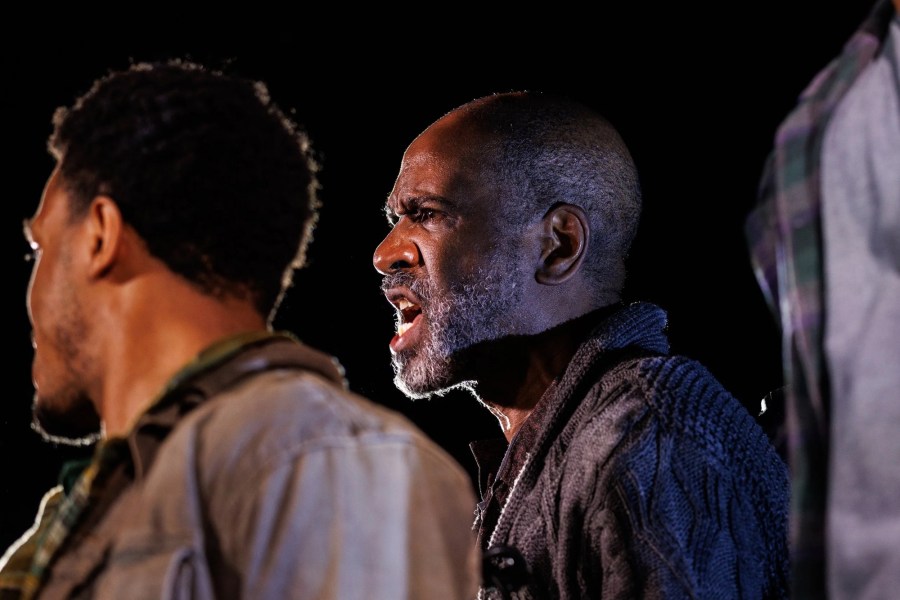

Case in point: Zora Howard’s Hang Time.

Given the fact that the central trio are already hanging over the stage as the audience enters, and given the play’s suggestion of their forever incarceration, the production could’ve left them up there as the audience filed out, a bookend that would’ve lingeringly stuck the audience with their everyman’s — Many Men’s? — eternally-unresolved state of constriction.

Instead, the curtain call interjects a last — and lasting? — image of liberation; we observe the actors free themselves from their shackles, before walking off stage of their own volition.

Hoi Polloi’s Winning is Winning exemplified the potential power — and then some — of depriving the audience of a curtain call. It’s unclear if/when the show is even over, blurring the demarcation line of reality/performance between on stage and off.

For anyone and everyone who rides for the theatrically abrasive, Alec Duffy’s Hoi Polloi deserves the completist treatment.